Seattle U Law At 50: Honoring The Past, Embracing The Future

Born out of a vision to provide high-quality and accessible legal education, the law school has thrived as a student-centered institution that values community

Over the past 50 years, an extraordinary community – nearly 13,000 strong – has emerged. They are lawyers and judges. They are U.S. attorneys, public defenders, prosecuting attorneys, and leaders of legal aid organizations. They are managing partners, business owners and executives, entrepreneurs, and politicians. They are pillars of the law throughout the Pacific Northwest, across the nation, and around the world.

The thread that weaves this community together is Seattle University School of Law. For five decades, the law school – first in Tacoma and now in Seattle – has provided students with the experiences and education that produced a talented and passionate cadre of alumni committed to high-quality legal practice and dignity, equity, and justice for all. A remarkable journey made this historic 50-year milestone possible and sets a strong foundation for the next half-century of legal education.

“NOTHING SHORT OF A MIRACLE”

The idea of establishing a third law school in Washington had been percolating among local leaders for several decades. It gained traction in the late 1960s when the University of Puget Sound (UPS) commissioned a feasibility study that identified Tacoma as one of the largest cities in the country without a law school. Demographic forces also came into play, with an increasing number of students seeking legal education, including Baby Boomers, returning Vietnam War veterans, and women.

Convinced of the need for greater access to legal education in the region, the UPS Board of Trustees voted overwhelmingly on Dec. 20, 1971, to approve the creation of a new law school. With classes scheduled to begin in September of 1972, the herculean task of launching the law school in just a few short months fell to founding dean Joseph Sinclitico, Jr.

Sinclitico, the former dean of the University of San Diego School of Law, had a daunting to-do list: hire faculty and staff, create and disseminate promotional materials, design a system to accept and review applications, admit the inaugural class, plan courses, locate a permanent home, and so much more.

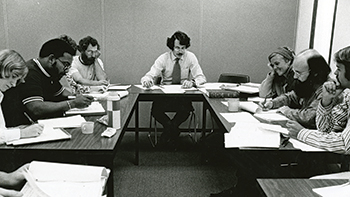

Despite the challenges, Sinclitico made impressive progress, bringing on board eight inaugural faculty members, including James Beaver, the only professor among them with actual law school teaching experience, and Anita M. Steele, the law librarian and sole woman among the initial hires. By June, the group had moved into a leased 30,000-square-foot building in the Benaroya Business Park on South Tacoma Way. Shattering expectations, 427 first-year students enrolled, easily surpassing the already ambitious goal of 335.

When Professor Thomas J. Holdych stepped to the lectern on the morning of Sept. 5, 1972, to teach the first class, the University of Puget Sound School of Law was officially born.

During that first year of operation, the law school received provisional accreditation from the American Bar Association (ABA), which noted in a report that “The University of Puget Sound may have set some sort of record in taking its law school from the ‘drawing board’ to the operational phase.”

About the provisional accreditation, Sinclitico reminded his colleagues that it was “not to be looked upon as a final phase but rather a first step.” And when the ABA granted the school full accreditation two short years later, the chairman of the law school’s Board of Visitors remarked that “the creation of the school has been nothing short of a miracle.”

BUILDING ON A STRONG FOUNDATION

A significant milestone was reached in August of 1974: 18 students enrolled in an accelerated program of legal education became the first graduates of UPS School of Law. The following spring, 91 percent of the August and December graduates passed the bar exam, confirming the high-quality legal education that would be the school’s hallmark. By the 1974-75 academic year, the school now had a full complement of 1L, 2L, and 3L classes in place for the first time, comprising 730 students, taught by 17 full-time faculty and supported by five librarians. Three legal clinics were also created a year later, marking the official birth of what would become the Ronald A. Peterson Law Clinic, the school’s highly regarded clinical legal program.

For Sinclitico, who had succeeded in launching the law school and building a strong foundation for the future, the time had come to step aside. The top priority for incoming dean Wallace Rudolph was to find a permanent home that would both meet the needs of the law school community and comply with ABA requirements that the university own, rather than lease, the law school’s building. With no endowment and little financial support from UPS, Rudolph turned to the City of Tacoma and its access to federal funding for urban renewal projects.

To qualify for this funding, the law school would need to find a downtown location rather than one on the UPS campus. The idea evolved into a proposal for a “law center” complex, which would house the Washington State Court of Appeals (Division II) and the Office of Assigned Counsel, as well as the law school. Students would benefit from the proximity to the offices of major law firms and agencies, along with county, state, and federal courts. As it turned out, the urban law center concept was integral to the development of a clinical program that would provide practical training to law students – placing UPS Law at the center of a growing national experiential movement spearheaded by U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Warren Burger.

The chosen site was the former Rhodes Department Store building in Tacoma, on the corner of 9th and Broadway, which at the time was abandoned and in need of extensive rehabilitation. With federal funds secured and combined with other sources, the building was transformed into the Norton Clapp Law Center, which opened in time for fall classes in 1980. At the dedication ceremony, none other than Chief Justice Burger attended, hailing the creation of the law center and the practical training opportunities its location afforded.

Given that the law school’s new home was a remodeled department store, it was not without its quirks. Students from that era fondly recall the centrally located escalator that led to the law library. The existence of a smoking room, complete with a Pac-Man arcade console, reflected the times. This was also when technology began to enter legal education and the practice of law. The library included one of the first-ever student computer labs in a law school, as well as dedicated LexisNexis and Westlaw terminals.

A PERIOD OF TRANSITION

For 20 years, the law school had been a part of the University of Puget Sound and integral to the legal community in Tacoma and the south Puget Sound area. That changed dramatically in November of 1993, when Seattle University announced it had acquired the law school. The reason for the transition in ownership was UPS’s desire to focus on undergraduate education, while Seattle U wanted to expand its professional education programs. Seattle U also understood the value of a law school as a powerful mechanism for activating its social justice mission.

Naturally, a change of this magnitude created a torrent of criticism and a cascade of questions and concerns. In the short term, students would earn their degrees from an institution to which they had not applied. Earlier UPS graduates would possess a degree from a law school that no longer existed. For some faculty and staff, a move to Seattle would be disruptive, both professionally and personally. Seattle U’s Jesuit Catholic identity also caused concern among the more secular-minded. The city of Tacoma and its legal community mourned the loss of the law school – a feeling that persists to this day – because it had brought a measure of prestige to the city, not to mention access to a first-rate law library and opportunities to work with law students.

Yet, as Professor Emeritus John Weaver (one of the founding faculty members) recalled, “It became clear that the problems that would have to be worked out [with the change in ownership to Seattle U] were far outweighed by the opportunities the new affiliation offered.” And to many in the law school, it felt great to be wanted.

At a ceremony in August of 1994 to mark the official transition, Seattle U Provost John Eshelman declared that “the future of the law school, and the future of Seattle University, is different from this day forward. I think it’s a much brighter and more exciting future.”

MAKING A HOME IN SEATTLE

Although the transfer was officially completed on Aug. 19, 1994, the law school continued to operate out of its home in downtown Tacoma. The ultimate plan was to move the law school to the Seattle U campus, which would entail an intensive process of planning, fundraising, designing, and construction that would take several years.

While that process was underway, the law faculty adopted a values-based mission statement reflecting the law school’s affiliation with its new institutional parent. Faculty and staff were deeply involved in committees to plan the new building and other important work to ensure a smooth transition.

In August of 1999, Sullivan Hall, the law school’s new (and current) home, named for former Seattle U President William J. Sullivan, S.J., officially opened just in time for the start of fall semester classes. Classroom chairs arrived only two days before.

In October, the law school organized a “Dedication Week” that welcomed 2,000 graduates and friends to visit Sullivan Hall. At the dedication ceremony, then-President Stephen V. Sundborg, S.J., called the occasion “a symbolic day that reaches beyond any of us, integrating the 27-year tradition of the law school with the 108-year-old tradition of Seattle University. What a powerful source of good it will be for our community.”

Dean James E. Bond, who had been serving his second stint as dean and was crucial in ensuring a successful transition to Seattle, stepped down at the end of the 1999-2000 academic year, and Rudolph Hasl assumed the leadership role.

In the years that followed, the law school experienced a run of prosperity, with record enrollments, buoyed by a strong legal job market. Now affiliated with a university committed to social justice, the law school undertook several initiatives, including creating the Access to Justice Institute, with a goal to build a community of equal justice-minded advocates and leaders within the law school. Next came the Fred. T. Korematsu Center for Law and Equality, named for the civil rights icon who defied orders to report to an incarceration camp for Japanese Americans during World War II and created to advance justice and equity through research, advocacy, and education.

During this time, the Legal Writing Program, which had been considered one of the law school’s strengths, was recognized as the top program in the nation by U.S. News and World Report; it has placed in the top 10 every year since.

In addition, the law school hired two successive deans who broke barriers. In 2005, Kellye Testy, a long-time faculty member, became the first woman to serve as dean, and in 2010, Mark Niles, a professor at American University Washington College of Law, became the first person of color to serve as dean.

STORM CLOUDS

The Great Recession of 2008 and its aftermath caused serious damage to many sectors of the economy, including the market for lawyers and legal services. With many law school graduates finding it difficult or impossible to land jobs, prospective students began to question whether law school was a good investment. Enrollment at law schools nationwide began to plunge, including at Seattle U Law, which struggled to enroll enough students to remain financially solvent.

Annette E. Clark ’89 became dean in 2013 at this challenging time. Although the recession had officially ended, application and enrollment numbers were still dropping across the country. This situation appeared to be the new normal, and she and her leadership team had to make difficult decisions if the law school was going to survive and flourish.

This meant slashing the size of the incoming class by a third, from 330 students to approximately 200, leading to a painful downsizing of staff and unfilled faculty positions, as well as a 50 percent reduction in the operating budget.

Through careful stewardship and the development of a multifaceted strategy, the law school’s financial picture improved considerably, aided in part by a much-needed rebound in the legal job market.

INTO THE FUTURE

Legal education is perpetually changing and adapting to the needs of the legal field. Seattle U Law has remained at the forefront by creating nationally renowned programs – clinics, legal writing, and externships – which help students become practice-ready immediately upon graduation.

That spirit of innovation drives the law school to continually improve and expand its offerings. In recent years, it has added graduate-level programs, including LLM degrees for lawyers and Master of Legal Studies degrees for non-lawyers, with an online-only option. The law school has also evolved its part-time evening program, a mainstay since its birth 50 years ago, into a hybrid-online program called Flex JD, which allows working professionals, those with family commitments, and place-bound students to access legal education.

After a nine-year tenure in which she shored up the law school’s foundation, Clark stepped down as dean. Anthony E. Varona, a former dean of University of Miami School of Law and vice dean of American University Washington College of Law, became dean on the cusp of the law school’s golden anniversary. As the next 50 years begin, Varona has articulated a bold and ambitious collective vision for the law school after extensive stakeholder consultation. His vision charts a course that is respectful of the history and traditions of the school, leverages its competitive advantages and opportunities, and ensures that it continues to deliver the best and most effective legal education in the nation.

The Diversity of Seattle U Law

Seattle University School of Law takes pride in its exceptionally diverse community, serving students representing a range of races and ethnicities, religions, nationalities, genders, and sexual identities. In recent years, significantly more women than men have enrolled.

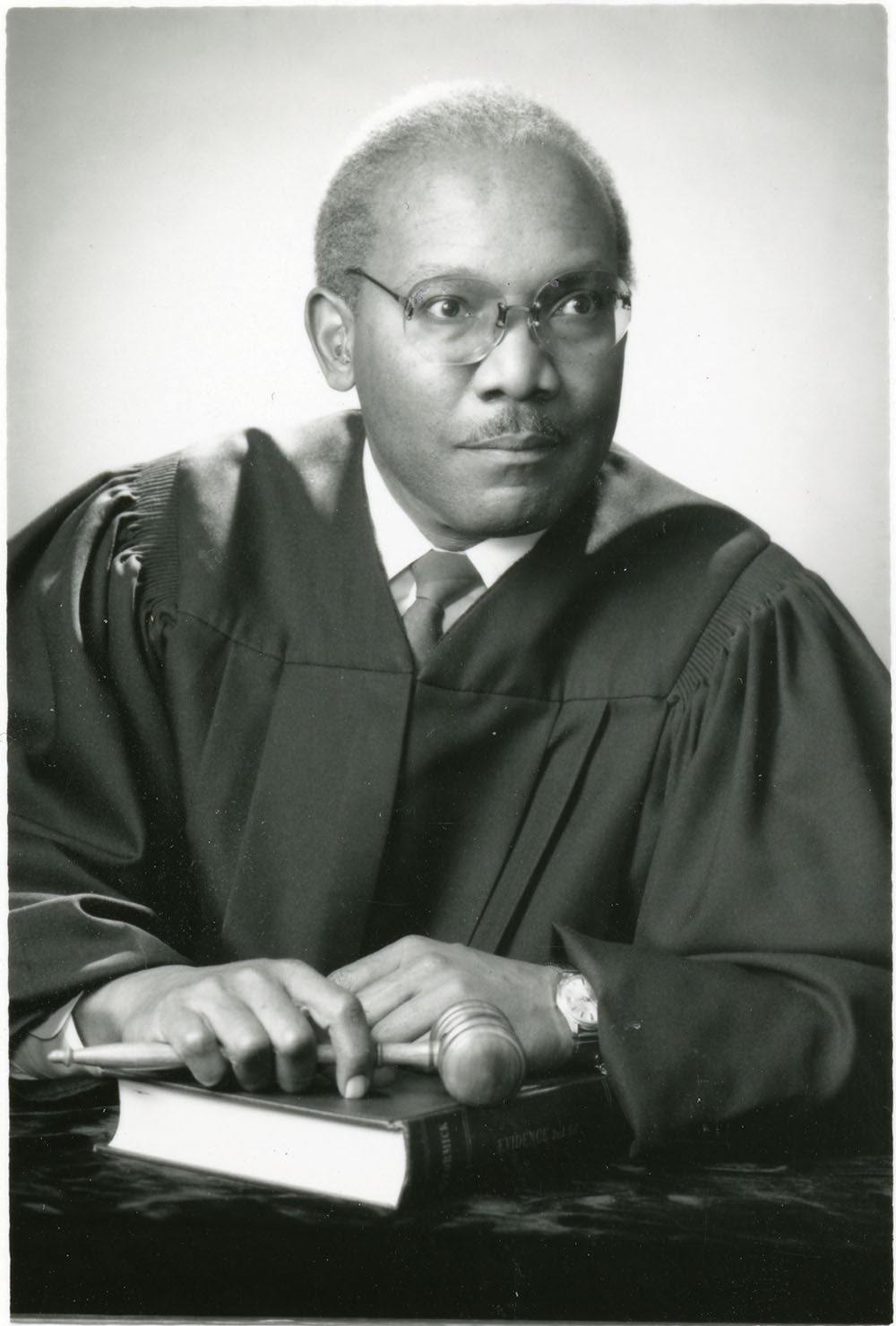

The law school wasn’t always so diverse, beginning as an overwhelmingly white and male institution, which was reflective of the legal profession at the time. Just 10 percent of the inaugural class in 1972 was female, and only a single Black student – Robert H. Russell – enrolled.

Even as many of the country’s institutions diversified, it wasn’t until 1994, more than 20 years after its founding, that the law school hired its first tenured professor of color, Henry McGee. And it was not until 2010 that the first dean of color, Mark Niles, was appointed.

Fortunately, the law school has steadily become more diverse. Out of the 231 students who comprised the 2022 first-year entering class, 57 percent were women; 37 percent were Black, Indigenous, or Persons of Color; and 32 percent were the first in their family to attend college. Twenty-eight percent identified as LGBTQ+. As a Latino immigrant and an openly gay man, new Dean Anthony E. Varona embodies this diversity.

These encouraging numbers are the result of progressive admission practices that are intentional about assembling incoming classes that are representative of American society. It’s part of the school’s determination to ensure that legal education is open to everyone, but particularly to those who are underrepresented in the legal profession.

This proactive work has helped Seattle U Law become one of the most diverse law schools in the nation and and these efforts will necessarily continue long into the future.

CONTACT

David Sandler

Director, Marketing & Communications

206-398-4108

sandlerdavid@seattleu.edu