This story originally appeared in Lawyer, Spring 2019.

When Lara Herrmann '00 founded the law school's Woman of the Year event almost two decades ago, she had a singular goal in mind.

"I saw it as an opportunity for female law students to align themselves with powerful women doing amazing things," she said. "Access to power is really key to determining a young woman's future in the law."

Nineteen years later, that annual celebration of women is still going strong — honoring exemplary members of the bar, bench, and beyond — and Seattle University School of Law is poised to send more female graduates out into the legal community than ever before.

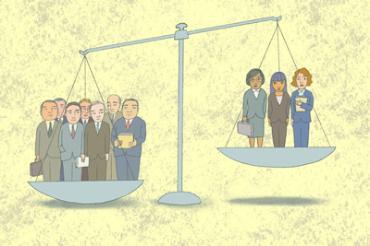

The class of first-year students for 2018-19 is 63 percent women; the entering class has been more than 50 percent women every year since 2013. For the law school as a whole, the student population is 60 percent women, making it the 13th highest in the nation in terms of female enrollment, according to an analysis of American Bar Association data conducted by Enjuris, a legal resource for personal injury attorneys.

Considering those numbers, what's the working world like that awaits these new lawyers after graduation? Are there equal opportunities for all? Is the future truly female?

We checked in with several law school alumnae to answer these questions, and they shared their successes, their frustrations, and their hopes for the next generation of female attorneys.

"I don't think I've ever been more excited about being a woman in this profession. We are leading the charge," Herrmann said. She and her father, Charles, now run a thriving personal injury practice in Tacoma that her grandfather started in 1950.

"I always wanted to see more opportunities for women, more doors opening. And now we have four highly qualified women with law degrees running for president in 2020. The biggest door is the door to the White House."

The U.S. Census Bureau reported last year that 38 percent of all lawyers in the country were women - an increase from 25 percent in 1990 and 4 percent in 1960. The statistics also show that 82 percent of female attorneys work full-time, year-round, compared to 63 percent for all other working women.

Closer to home, women also found reason to be optimistic about the state of the legal profession in Washington. Six of the nine state Supreme Court justices are women, including the chief justice, and 44 percent of all judicial officers in the state (as of 2017) are women, according to Washington Courts.

And, very recently, Mary Robnett '91 took office as the first-ever female Pierce County Prosecuting Attorney. Her swearing-in was greeted with a standing ovation at the County-City Building.

The Washington Supreme Court Gender and Justice Commission also works to promote gender equality in the legal profession, supporting female students at all three of the state's law schools with scholarships, networking, and mentorship.

Even as representation improves, women attorneys still face daily reminders that it's a work in progress. Several alumnae shared similar stories: They're often mistaken for court reporters. Opposing lawyers call them "honey" or "sweetie." They're mocked, even by judges, if they get emotional. Jurors comment on their hair and their clothes.

Michele Radosevich '94, now a partner at Davis Wright Tremaine LLP, served as president of the Washington State Bar Association in 2012 and has also worked as a lobbyist and as a state senator in Wisconsin. She said the atmosphere for women can vary depending on the workplace.

Government agencies are more responsive to social change and make a greater effort to both recruit and accommodate women and minorities, she said, because they have to answer to the electorate, which is half women. Private law firms answer to clients.

"A law firm can have the best of intentions, but often it's about the clients. If a client has a question, they expect you to respond immediately, even if it's 8 o'clock at night and you need to get the kids to bed," she said. "And that's not nice for the dads of the world either."

Stereotypes about both lawyers and women can also come into play. A client might insist that the only way their lawyer can be effective is to be highly aggressive and that a woman can't be that kind of lawyer.

"There have been times, after interviewing with a potential client, that it was clear I didn't fit their idea of what they needed and it had to do with me being a woman," Radosevich said. "But anyone who thinks hiring an attack dog is the only way to win isn't going to get the best outcome. Any good lawyer will tell you that you need a complete toolkit."

Of course, clients can also be allies. Cori Gordon Moore '98, a litigation partner at Perkins Coie's Seattle office, credits many locally based companies with encouraging an inclusive and progressive atmosphere among the law firms they hire.

"Our local corporate citizens have been very proactive in creating opportunities for women and people of color," she said. "They expect that their legal teams be diverse, because that's the face of their company."

In fact, Moore said that thanks to the progressive atmosphere at her firm, she hasn't felt limited in any way by gender.

"I honestly feel like I'm part of the first generation of women — in the way I was raised by my parents, in the schooling I received — to believe and expect I could do whatever I wanted professionally," she said.

Alumnae who have practiced elsewhere reported that Washington, especially Seattle, can feel more egalitarian than other places.

Shantrice Anderson '14 practiced public defense in Colorado Springs, Colorado, before returning to Seattle to practice maritime law. She said she once had a client who ignored her and referred to her only as "she" and "her" rather than by her name. Some clients would only listen to her ideas if she brought a male colleague on the case to back her up.

"Talking with other women was huge for me because when these things happen they're so small and so slight that you feel like you're going crazy," she said. "But all of my friends from law school go through the same thing and we all practice in different areas."

For Judge Stephanie Arend '88 of Pierce County Superior Court, her encounters with sexism in the legal profession have helped make her a better judge.

"I certainly have had moments where I felt slighted or treated differently, but I don't want that to be my story," she said. "I try to remember what those moments felt like and I try to be mindful of treating people who come in front of me the same - men, women, indigent clients, everyone."

Whether it's a monthly lunch outing with female friends or a more formal mentoring relationship, alumnae agreed that it's important to have an outlet for discussing the unique challenges and rewards of being a female lawyer. For Charisse Arce '14, now an assistant U.S. Attorney in Anchorage, Alaska, that guidance started in law school.

She remembered a moment after her appellate argument in legal writing when the judges' questions had been especially tough. Sara Rankin was her professor at the time.

"I was demoralized by how I did in the questioning, and I started to cry at the end. I thought, 'Oh, I'm just being a girl and getting overly emotional,' but Professor Rankin saw it happen and we talked about it," she said. "Now, I'm an attorney and I get beat down in court but I don't take it personally. I know it's not about me. She was instrumental in me being able to understand that."

Lauren Parris Watts '11, a partner at Helsell Fetterman, has received valuable support and guidance from both male and female mentors over the years, especially as she worked to improve her law firm's parental leave policies. Maternity leave was previously covered only by short-term disability, but now, thanks to efforts by Watts and others at the firm, both male and female employees get six weeks of paid parental leave for the birth or adoption of a baby (in addition to short-term disability and other types of leave).

Watts said part of what drives her to advocate for change is her interest in having everything spelled out ("I'm a millennial! We like transparency."), but also an interest in including all genders and all levels of employees, from staff to partners. The barrier, she said, isn't outright hostility. It's more a lack of perspective.

"Partnerships are still predominantly white straight men who are very well-intentioned and who want to do the right thing, but they haven't lived their life as a young mom who's a partner or as a black woman who's the only woman in the room at a meeting. They don't have that experience," she said.

"When I propose a policy change, I have to explain that. How does it feel to be the only woman in the room? How does it feel to look up into the partnership and not see anyone who looks like you?"

Moore said her firm, Perkins Coie, regularly schedules a women's retreat for female attorneys to discuss everything from marketing to how to allocate billable and non-billable hours. They're the same sorts of issues all lawyers talk about.

What the retreats don't usually focus on, she said, is children. Parenthood is not just a women's issue, and not all women are mothers.

"Gender is something women obviously have in common, but it's a mistake to assume that we're all going to think alike or that we all have the same issues," she said. "What's important is how can we support each other, how do we ensure we have a voice, and how can all of our women lawyers feel empowered."

And that's exactly the feeling Herrmann was after when she created the Woman of the Year celebration. With technology and social media, she said, women have a larger platform than ever before to share their empowering experiences.

"I see doors opening left and right for women," Herrmann said. "It's important for them to understand how much power they have with a law degree."

Anderson echoed that sentiment. Even though she's often the only woman in the room in a male-dominated field like maritime law, she's there. And that's important.

"The biggest thing for me is just having a presence. Being a woman of my age in a room with men who are significantly older than I am — I'm the same age as their children! — it feels really cool to know that I've made it there," she said. "Our generation is coming up. We can be in these spaces and we can change the face of the profession."