Students in Seattle U Law's International Human Rights Clinic scored a victory for a Tacoma man who was wrongfully imprisoned abroad

This story originally appeared in Lawyer, Spring 2024.

More than a decade after U.S. citizen Jason Puracal experienced a nightmare of wrongful imprisonment and abuse at the hands of the Nicaraguan government, he is closer to seeing justice served in his case. This is thanks in large part to the years-long effort of Seattle University School of Law Professor Thomas Antkowiak and students in his International Human Rights Clinic to hold the government accountable.

This past winter’s 50-page decision from the Inter-American Commission (IAC) on Human Rights affirmed that Puracal’s human rights had been violated. That decision has been sent to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, which is almost certain to uphold it.

“The IAC is part of the Organization of American States, which is similar to the United Nations, but just for the Americas,” explained Seattle University School of Law Professor Thomas Antkowiak. “The IAC is very influential and has had success in bringing about changes and reparations in other countries.”

This victory would not have been possible without the clinic, which provides pro bono legal representation to clients who have suffered wrongful imprisonment, torture, and displacement. More than a dozen of Antkowiak’s students spent two semesters 11 years ago creating a 100-page complaint detailing the inhumane treatment of Puracal, who grew up in Tacoma.

“The commission’s decision was the first time that Jason’s whole story and everything his family suffered was formally and officially recognized to be wrong and illegal,” Antkowiak said. “This has been long-awaited. It’s a testament to the dedication and hard work of our clients and the students.”

The saga began in 2010, in the coastal Nicaraguan city of San Juan del Sur, where Puracal had settled after a stint in, the Peace Corps had initially brought him to the area. It was now his home, where he met his wife, had a son, and built a business. As Puracal was wrapping up his work one evening, a dozen armed, masked, and Kevlar-clad men burst into the office.

Puracal first thought he was being robbed, until a police officer placed him under arrest. Held at gunpoint for hours, with no idea what he was accused of and no ability to contact an attorney, Puracal watched as the men seized his computers, files, and even his car before they violently hauled him to jail.

“I thought, ‘They have the wrong person, they have me confused with someone else,’” he recalled.

Puracal was taken to El Chipote, a notorious prison used by Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega to silence his political opponents.

“Jason’s is one of many cases where people are wrongfully convicted, repressed and persecuted in Nicaragua,” said Antkowiak.

Puracal was stripped of his clothing and forced into a windowless cell filled with garbage, excrement, and insects. Women down the hall screamed that there was a snake in their cell.

“I could hear people being tortured and beaten,” he recalled.

It was days before Puracal learned he was charged with international drug trafficking, money laundering, and organized crime, even though he did not possess any drugs, could vouch for all of his business’ funds, and had never met the individuals with whom he allegedly conspired.

“Even waiting for trial, I thought they had me confused with someone else,” Puracal said. “If you come from the U.S., you have this sense that the justice system will operate in a way that is fair and equitable, it will sort this out, and they'll let me go, because I haven’t done anything wrong.”

After a trial nine months later where Puracal’s attorney was not allowed to present photo or video evidence, the prosecution could put forth false stories obtained from unidentified witnesses, and the judge was himself wanted for fraud in another case, Puracal was found guilty and sentenced to 22 years.

A year later, after international media drew attention to Puracal’s plight, the decision was reversed on appeal. However, the government seized his property and deported him. This meant tearing Puracal’s wife from her relatives and country, and his son from the only home he had ever known.

The International Human Rights Clinic steps in

Spearheading the media campaign for her brother inspired Janis Puracal ’07 to transform her career from a civil law practice.

“Now I focus on preventing wrongful convictions before they happen,” said Puracal, who directs the Portland-based Forensic Justice Project. “On days when it’s really difficult, I’m reminded that there’s somebody’s family member on the other end of that.”

Post-release, she was not done seeking justice, so she turned to her alma mater.

The clinic asserted violations of six articles of the American Convention of Human Rights to seek reparations for Puracal and his family. In preparing the 100-page complaint, students interviewed the Puracals, prepared declarations, drafted legal arguments, and conducted research into international legal precedents and human rights reports in Nicaragua, all of which was translated into Spanish.

“They were doing some really sophisticated legal work,” Antkowiak said. “Aspects of the case concerned novel areas of the law.”

Students created groups to each tackle a different convention article to prove that Puracal’s rights had been violated.

Molly Matter ’15 reported on Article V, the right to humane treatment in prison, describing the horrors that Puracal faced. Housed alongside violent offenders, Puracal was confined in crowded cells with just a hole for a toilet and an insect-infested bucket of water for drinking and washing. Forbidden from going outdoors for seven months, he lost 40 pounds, incurring malnutrition-related health problems. After burning himself while attempting to boil water, he contracted sepsis from unsanitary medical instruments and nearly lost his legs.

Interviewing Puracal about the inhumane prison conditions was not easy, but it prepared Matter for the secondhand trauma that often accompanies a career in human rights.

“I go into prisons and immigration detention centers. I see human suffering,” said Matter, who now runs a solo human rights practice, Amend Law. “It was helpful to get that real lawyering experience and test out if I really could do this.”

Whitney Phelps ’13, worked on Article VII, the right to personal liberty, as a clinic student.

“A lot of what I learned in the clinic, being trauma-informed in how we interact with clients, is something I’ve carried into my practice,” said Phelps, who now works as a Portland-based immigration attorney and often counsels Nicaraguan asylum seekers.

It took a decade — drawn out, in part, by COVID delays — but the IAC's decision was “exactly the type of result we were hoping for,” according to Antkowiak. In validating each of the clinic’s points, the commission called for reparations, including fully compensating Puracal for all material and personal damages, including physical and mental health care costs, and, importantly, ordering the government of Nicaragua to adopt laws ensuring similar human rights violations can never happen again.

The Inter American Court, where the case will be heard, is likely to order more expansive reparations than the IAC, including specific amounts of money, with a one-year timeline for Nicaragua to obey.

“The court has more force because it’s a binding court, the highest authority in the Americas, and there’s no appeal,” Antkowiak said, noting that he is hopeful because the court has a successful track record of obtaining compliance from many countries.

For Puracal and his family, who to this day struggle with PTSD, the ruling does not truly compensate for their trauma, but it does provide a sense of justice.

“Once you’re incarcerated, whether rightfully or wrongfully, there’s always a stigma that follows you around. I’m still struggling to put my life back together, to get my family the financial stability and peace of mind we used to have,” Puracal said. “This decision feels like a vindication. I hope the government of Nicaragua will do the right thing.”

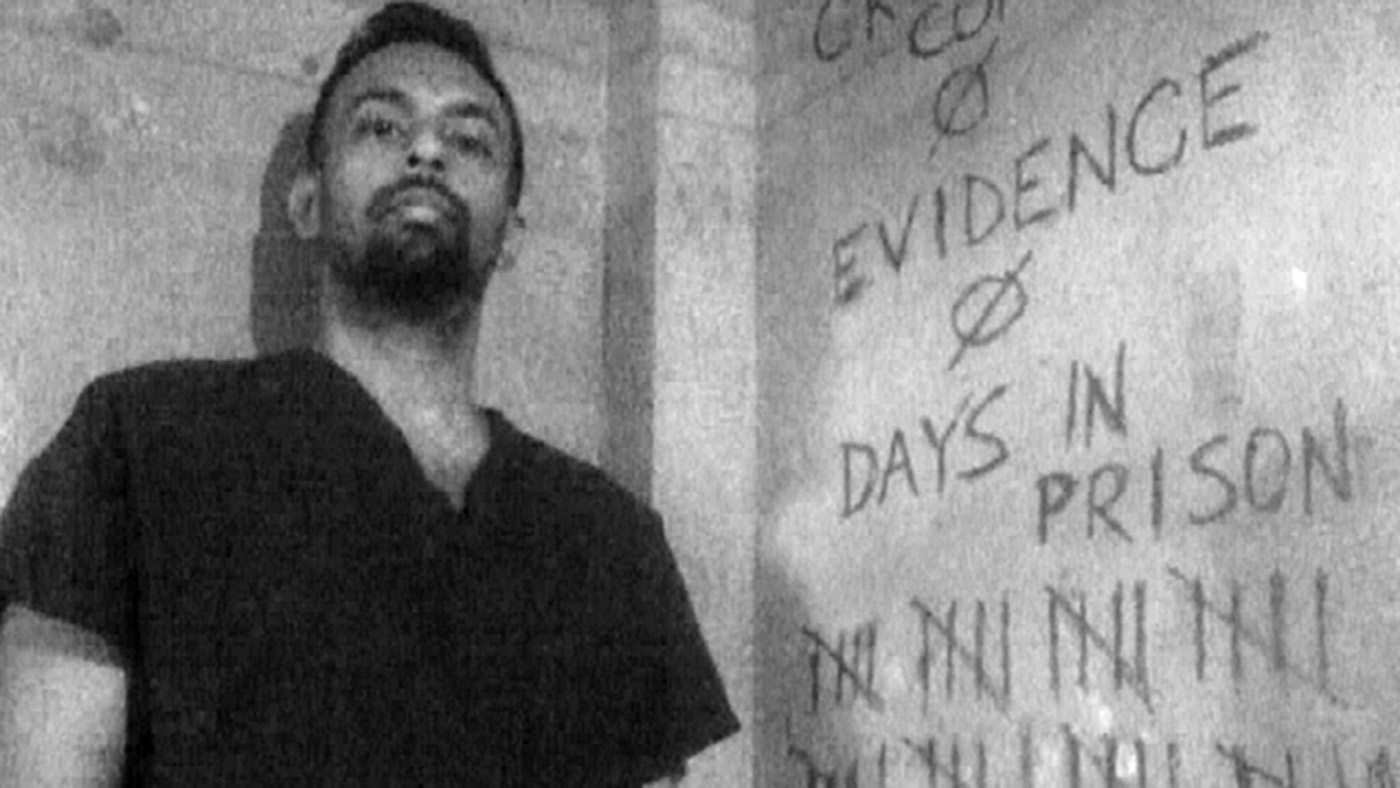

Photo caption: Jason Puracal snuck a camera inside of a pen into his cell to document the horrific conditions of the prison. Here, he demonstrates the number of days he had been locked up at that point without any credible evidence linking him to the crimes with which he was charged.

Photo caption with students: Jason Puracal visits the International Human Rights Clinic every year to speak to students about his harrowing experience and encourage them to seek justice for those who are persecuted.

Photo caption with Tom: Jason Puracal and Professor Thomas Antkowiak, who directs the International Human Rights Clinic, have remained good friends ever since the clinic first took on Puracal’s case more than a decade ago.